Counter-Storytelling as a Resistance Tool in Anti-Racism Education: Reclaiming African Immigrant Children’s Identities

Congratulations to PhD student, Kamogelo Amanda Matebekwane, who was recently awarded a Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). Amanda’s research focuses on co-researching with African immigrant children and their families to understand how they construct their identities in the context of anti-racism education in elementary schools in Canada.

“I’m genuinely grateful to the Faculty of Education, the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research, and to SSHRC) for their scholarship and to all for supporting my studies.” - Kamogelo Amanda Matebekwane, PhD student, Faculty of Education, U of R

Kamogelo Amanda Matebekwane was born and raised in the Republic of Botswana and migrated from southern Africa to Canada in March 2017. As a Black woman, mother, immigrant, and critical researcher, Amanda brings a unique perspective to her research.

Critical race theory is an academic concept with the core idea that race is a social construct, and that racism if not merely the product of individual bias or prejudice, but also something embedded in legal systems and policies.1

Amanda’s doctoral program is inspired by critical conversations with immigrant families. Listening to their stories and experiences, she learns how they deal with microaggressions as Black people. Her research is rooted in critical race theory and one of the tenets is counter-storytelling.

“We are very proud of the success of Amanda for winning this esteemed and competitive award. This remarkable accomplishment recognizes the high calibre of the work that Amanda is undertaking.” - Dr. James Nahachewsky, Dean, Faculty of Education, U of R

Join her today in this interview, as she shares her stories and observations on how counter-storytelling can be adopted by educators.

Question: As a Black parent and as newcomers to Canada, do you feel supported raising a family here?

Amanda: I never thought, as a parent, I would have a heavy burden of reminding my children daily to stay low and be quiet when police officers pull them over or speak to them. I never thought I’d live in fear for my children every morning when they stepped outside their home, reminding them not to put on their hoodies while walking in the neighbourhood because someone might call the police on them. My youngest children more often share how their teachers ignore them in classes when they raise their hands to participate. Sometimes, they nearly have accidents because they have been raising their hands for a long time.

I am aware that many African immigrant families resonate with my family’s experiences. Unfortunately, it comes back to us, Black parents, to do extra work to make sure that our children are safe and at least survive the hostile environment in which they grow up. However, I hope Regina will someday become a welcoming city where immigrant families feel at home and prosper. While Regina is beginning to feel more at home, these experiences impede the prosperity of belonging.

On a positive note, I am humbled to have my family live in a safe environment with supportive neighbours and community. Places like Regina Open Door Society assisted us with finding schools for our children. Regarding finding job opportunities, kind friends from my church community recommended SaskJobs to review my résumé and upgrade it to Canadian language and standards, while the governments of Canada and Saskatchewan are supporting my studies through student loans and grants. Also, my children have established amazing friendships in their schools, reassuring us about their positive experiences here and giving us hope for their future.

Question: In “Counter-Storytelling: A Form of Resistance and a Tool to Reimagine More Inclusive Early Childhood Education Space” (in education, 2022) you talked about the normalized practices in education that continue to marginalize the minority community. You have specifically pointed out that story is powerful (i.e. creating picture books as a practical tool to tell children’s own stories). Are you advocating for such activities to a wider group?

Amanda: My doctoral program is inspired by engaging in critical conversations with immigrant families and listening to their stories and experiences and how they’re dealing with microaggressions as Black people. Equally important, I’m always in awe of their coping mechanisms and stories that bring hope to Black folks navigating white-dominant spaces. Realizing how powerful stories are, I became curious to learn more about storytelling. During my readings, I learned about critical race theory, one of its tenets being counter-storytelling. More often, the experiences of racialized communities are told by the dominant group, and mostly, these stories are ingrained with stereotypes, biases, and racism. Usually, as these stories dominate in society, the lived experiences of marginalized people are silenced, ignored or considered unworthy.

My article explained counter-storytelling as a resistance tool that challenges the dominant stories. Even though the context was in education, counter-storytelling has implications outside education that restore validation for marginalized communities. Since the tool foregrounds the experiences of marginalized communities while naming the micro-aggressions and racism embedded in society, other fields, such as counselling, can employ counter-storytelling with youth to enhance their positive well-being and build resilience (i.e. through art-based therapy).

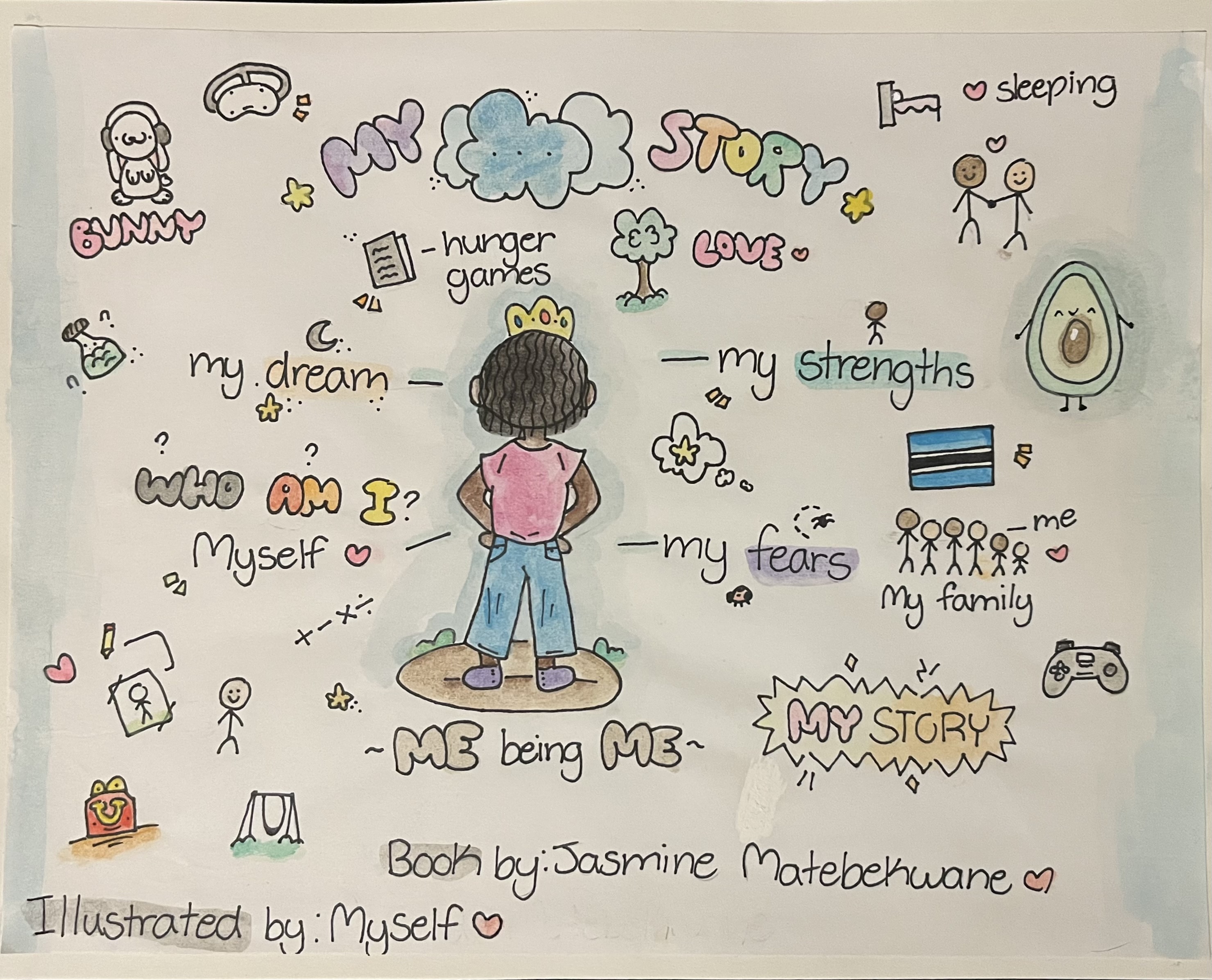

In a school context, Black children are labelled and put in a specific category based on their skin colour. Mostly, this category is unpleasant, unfavourable, isolated, discriminatory, and hopeless for the educational attainment of racialized children. As a mother, I advocate for interventions that help our children survive the hostile environment and be proud of their identities. Humans are narrative creatures. We are all storytelling beings. A picture book is one of those interventions I use with my children. My 10-year-old daughter is an exceptional artist who works on a picture book that shares her story. Most of her pictures express how she views herself, and that’s a powerful tool for reclaiming her identity as a young Black girl.

“Kids are talented in many ways—digital literacy, theatre, poetry, journaling—and they can use such talents to share their stories to claim their identities.” - Kamogelo Amanda Matebekwane, PhD student, Faculty of Education, U of R

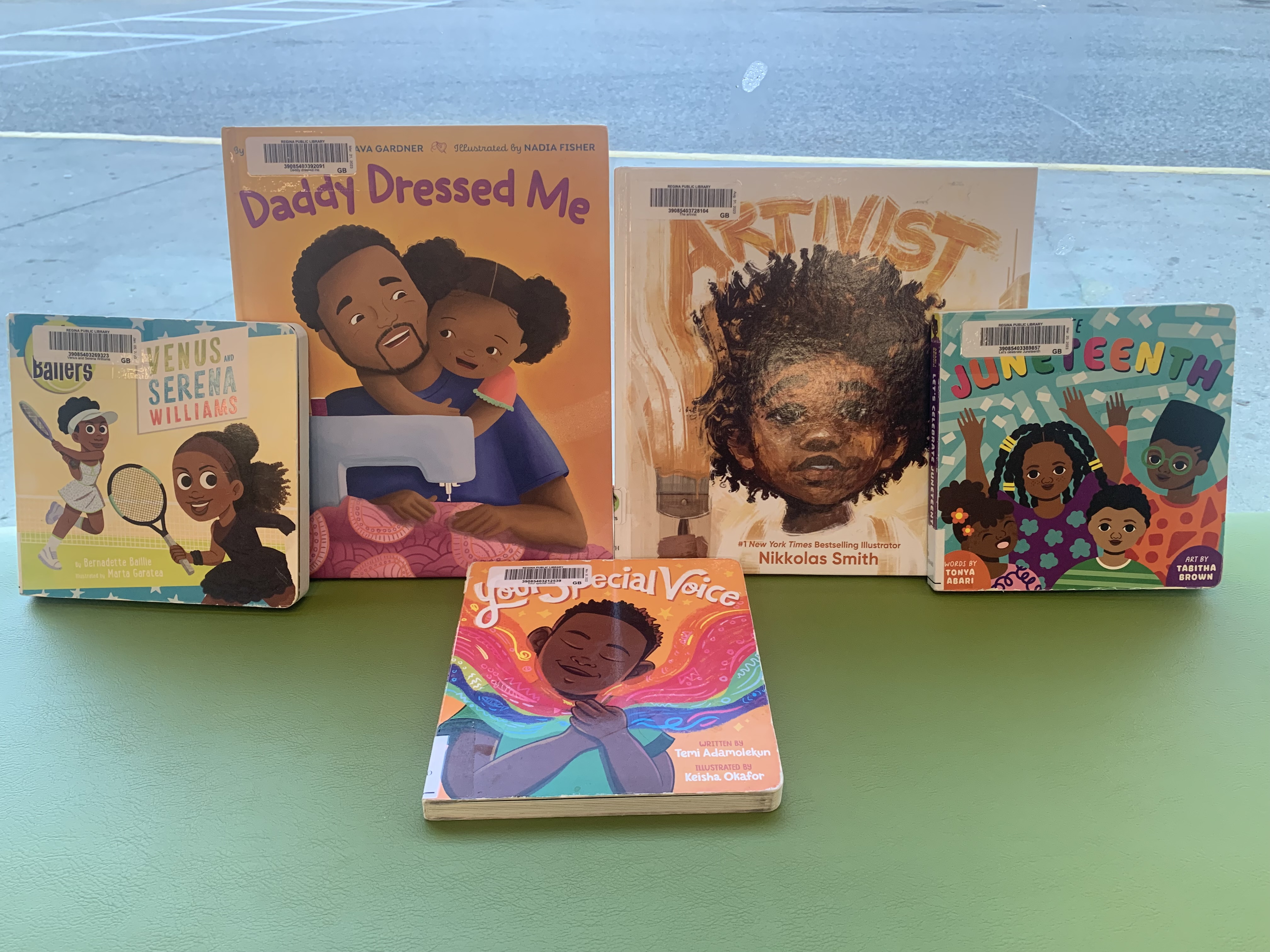

Similarly, teachers can welcome classroom counter-stories to rearrange the curriculum based on students’ experiences and perspectives. I was intrigued by some of the teacher's efforts and dedication to welcoming immigrant children’s experiences by asking them to share their concerns in their local community. When kids bring their experiences and share with their classmates, the teachers would use their narratives and perspectives to design curricula around such issues to solicit their ideas to address social justice. Also, teachers use critical literacy to welcome counter-stories of children while challenging the status quo and the dominant narratives found in children’s literature.

Alyse C. Hachey (Department Co-Chair) and So Jung Kim (Associate Professor) in Teacher Education at the University of Texas at El Paso, conducted a study in South Korea for their 2021 article, “Engaging Preschoolers with Critical Literacy through Counter-Storytelling.” The study examined how preschool-aged children negotiated, represented, and (re)created their voices by engaging in counter-storytelling about fairy tales.In the study, the children were given opportunities to playfully manipulate the original story using their creativity and imagination, at the same time exploring unheard voices and multiple viewpoints. The children played with themes and messages embedded in the fairy tales and recreated the stories using their own voices through drawing. For instance, when the children and teacher explored a Disney Cinderella storybook, children offered alternative endings of Cinderella in a critical and creative way. The children deconstructed the ending of the story and shared that Cinderella could have overcome her hardship through acquiring a good education. This example indicates the power that young children have to challenge the status quo and magnifies the discrimination that is interwoven in the teaching and learning materials. According to the authors of the study, counter-storytelling activities “offer a rich context in which young children practice deconstructing the dominant discourses, learn to tell their own stories and learn to listen to the stories of others”.

Question: What is your advice for parents to encourage their children to take pride in who they are?

Amanda: Immigrant children are struggling to find their place in this white-dominant space. My study intends to adopt strength-based approaches when co-constructing knowledge with African immigrant children and their families. I believe that for transformation to take place in children’s educational realities, we need to identify and name the challenges they’re experiencing at school and find interventions to mitigate them. For instance, one approach could be to demystify the student’s culture by shifting from the colour-blind approach to meaningfully engaging with the students’ families to learn more about their cultural values, practices, and expectations. Literature has indicated that there is a mismatch of beliefs and practices between white teachers and immigrant children that causes language barriers and eventually disconnects children from learning. Eventually, the disconnection can lead to harsh discipline and mistreatment of marginalized children.

So, I believe transformation is a two-way street whereby racialized parents and schoolteachers work collaboratively to share their expectations while, at the same time, becoming knowledgeable about cultural differences that will mitigate ignorance and cultural deficits in their classrooms.

Daily praises and encouragement are very powerful because they manifest in marginalized children’s mindsets so that even though they are being challenged by racist and discriminatory behaviours in their spaces, they can still see the positive in themselves. I always tell my kiddos, “You look so beautiful,” or “Be strong and brave.” Because I know that if I don’t praise and encourage my children, they will seldom receive any positive feedback from the society.

Question: Could you briefly share your current projects?

Amanda: I am currently completing my proposal and applying` for ethics approval. I’m working with the Faculty of Nursing in data collection and qualitative data analysis to explore the experiences of Black undergraduate nursing students and registered nurses in Saskatchewan. I’m also assisting my supervisor, Dr. Donna Swapp, in quantitative data analysis to understand the experiences of Black engineers and students in Canada. I have the privilege of presenting some of the projects at local and international conferences while working on several publications from those projects and my work. I’m currently engaged in knowledge mobilization with Dr. Swapp on a project around the work of Black school leaders in Saskatchewan, specifically a conference presentation in Los Angeles and a pending publication.

Question: Why did you choose the University of Regina for your graduate studies? Did any specific support systems or resources at the U of R make an impact on you and your experience?

Amanda: One of the reasons I chose the University of Regina was the decolonizing, anti-racism, and anti-oppressive education offered in graduate studies. When I came to Canada, the first few months were unsettling. As a newcomer, I couldn’t understand the behaviours of the salesclerks following me around the store or when white people assumed that I was a service worker because of my skin colour.

An eye-opener for me was the anti-oppressive education course taught by Dr. Michael Cappello and Dr. Twyla Salm in my master’s program, where I learned about micro-aggressions and racial profiling. I was inspired to enrol in my doctoral program to engage more in critical research. Another pivotal juncture was a Directed Reading course I took with my former supervisor, Dr. Emily Ashton, titled “Blackness as Presence in Early Childhood Education,” which allowed me to engage with critical readings that addressed decolonizing and anti-oppressive education.

Check out the programs offered by the Faculty of Education

Through my research assistantships, I have chosen to engage in anti-oppressive projects that identify and challenge the prejudices and white supremacy embedded in society. Also, I interact with students, faculty members, and people committed to social justice to learn about their experiences, which nourishes my critical growth and understanding as a scholar and Black person. Also, through my indispensable readings and profound interactions with critical scholars, I am in a better position to prepare my children to navigate the racist and discriminatory spaces in which they live and attain education.

Equally important, my supervisor, Dr. Swapp, and committee members have supported and advanced my critical positionality and continue to offer me invaluable guidance to help me thrive in my doctoral program. I’m genuinely grateful to the Faculty of Education, Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research, and The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) scholarships for supporting my studies.

Question: Based on your experience, what advice would you give other grad students?

My advice to my fellow racialized students would be whether you are at undergraduate or graduate level, you cannot do this alone. Instead, nurture a strong relationship with your supervisor, find a supportive community, find your community, and be in community. We should remain hopeful that things will change for the better. To white students and educators, I encourage you to be active social justice teachers and educators who are open and attentive to all multiple forms of oppression while working to disrupt these oppressive structures, culture, and practices. Only through effort and action will your classrooms become inclusive learning spaces that nourish the interest and well-being of all children regardless of their race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and religion.

Important to note: It has been estimated that by 2041, in Regina, the proportion of persons from racialized groups is projected to increase from 18% to 41% (Statistics Canada, 2022). The unique and complex identities of immigrant children have not only raised a challenge, but also presented tremendous opportunities to our education. In 2023, the not-for-profit organization People for Education, in a publication entitled “A progress report on anti-racism policy across Canada”, reported that while 73 per cent of schools included anti-racism and equity in their school improvement plan, only 28 per cent of school boards have implemented an anti-racism policy, strategy or approach. Becoming knowledgeable about cultural differences will mitigate the ignorance and culture deficits in the classroom. Our researchers, in small and incremental ways, are working to reimage and reconstruct safe education spaces that rejoice in human diversity - for the well-being of our children.

1.Education Week, “What Is Critical Race Theory, and Why Is It Under Attack?”, Stephen Sawchuk, 2021