When you think about Canadian Western Agribition, you might picture cattle, horses, and the rodeo.

What about science?

The University of Regina’s Biology department arrived at Agribition last week ready to show just how much science can do for the Saskatchewan agriculture sector. From protecting livestock and improving water quality to detecting pathogens and fighting invasive weeds, researchers and students from four U of R Biology labs shared tools and research helping to support farmers, ranchers, and communities across the Prairies.

Left to right: Ashlyn Kirk, U of R alumni and current lab manager for the Institute for Microbial Systems and Society; Dr. Kerri Finlay, U of R professor and director of the Institute of Environmental Change and Society; Ryan Rimas, Biology PhD candidate in the Finlay Lab; and Jessica Smith, U of R alumni and research associate in the Finlay Lab, at the Biology Department’s Agribition booth. Credit: Photo credit: U of R Communications & Marketing

Wrangling water problems before they buck

Water quality can have life-or-death consequences for livestock. In 2017, high salinity, meaning unusually high levels of dissolved salt in water, was linked to the deaths of more than 200 cows in Saskatchewan.

Enter the Finlay Aquatic Sciences Team (F.A.S.T. lab), led by Dr. Kerri Finlay, U of R professor and director of the Institute of Environmental Change and Society. The F.A.S.T. lab has developed tools that help communities, farmers and ranchers better understand and protect their local water sources.

At Agribition, the team showcased Cow Kits, a practical, easy-to-use tool that gives farmers and ranchers a quick way to check salinity levels in dugouts and ponds, so their livestock have safe drinking water. They also shared information about water-monitoring kits provided through the lab’s partnership with Water Rangers, a Canadian non-profit organization dedicated to expanding community-based water monitoring. The Water Rangers kit lets community members assess the health of their lakes, providing valuable information that supports better water management and helps keep recreational waters safe.

Through their research and outreach, the F.A.S.T. lab is helping producers and communities across the Prairies meet today’s water challenges.

This town ain’t big enough for the Canada thistle

Canada thistle, a notorious outlaw, is one of the toughest weeds for organic producers, who can’t rely on chemical herbicides. It spreads quickly, competes with crops for light, water, and nutrients, and its populations have risen steadily across the Prairies over the past decade, leading to significant yield losses.

Dr. John Stavrinides, U of R professor and head of the Biology Department, is exploring a solution to send this weed packing. At Agribition, his team shared their research on an organic bioherbicide, a naturally occurring bacterial pathogen that infects Canada thistle and a few other similar weeds. Once inside the plant, it causes bleaching, stunted growth, and reduced flowering, making the weed far less competitive in farmers’ fields.

Early field studies are promising, and the Stavrinides lab is refining single-strain and mixed formulations to strengthen the bioherbicide and exploring proactive applications that target shoots before they emerge. The end goal is to create an affordable, organic bioherbicide that tackles Canada thistle without chemicals, protecting crop yields and increasing profitability for producers.

Canada thistle may be tough, but the Stavrinides lab is tougher.

Protecting the roots that feed the Prairies

Not every threat in the field is visible. Some begin in the soil.

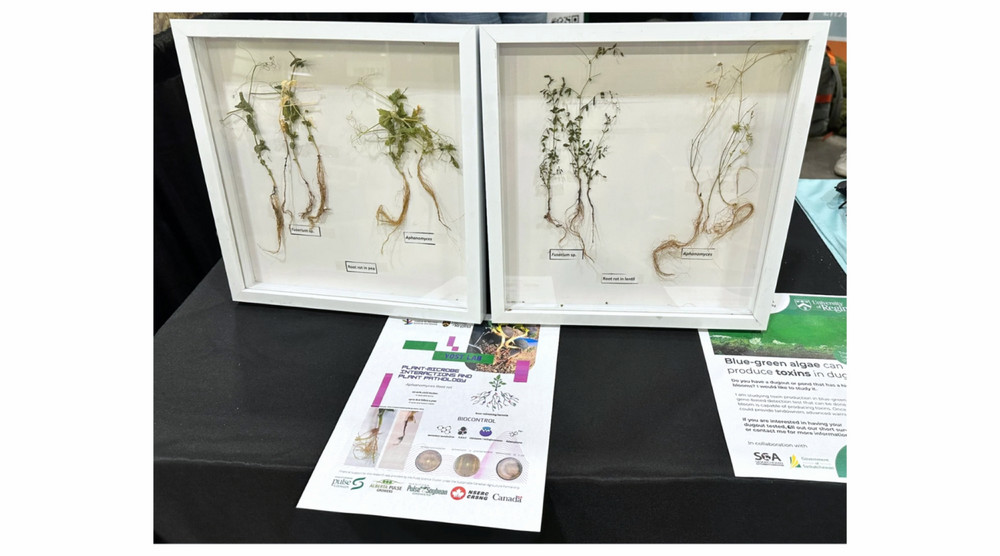

Root rot complex is a group of soil-borne pathogens impacting plant roots and has been found in 99 per cent of fields across Canada. One of its worst offenders is a pathogen responsible for devastating losses in peas and lentils, causing up to $1.5 billion in sales and export losses across Saskatchewan alone.

Currently, there are no effective solutions against the pathogen because it is resistant to fungicides and its spores are very hard to eliminate. The only viable option farmers have is crop rotation, which can span eight to ten years.

Dr. Chris Yost, U of R Vice-President (Research), professor, and co-director of the Institute for Microbial Systems and Society (IMSS), is working to change that. His lab is researching natural, environmentally friendly biocontrols, microorganisms capable of slowing the growth and development of the pathogen. These microbes may offer an alternative for farmers who have few tools left in the fight.

At Agribition, postdoctoral researcher Edgar Mangwende and graduate student Rafa Grajales shared this work with producers. Through Yost’s lab, they are currently examining how these biocontrols perform under real-world field conditions to better understand how they work and to help bring a treatment to farmers struggling with these pathogens.

With Yost’s lab digging in, root rot complex may have finally met its match.

A display from Dr. Chris Yost’s lab at Agribition showing pea and lentil samples affected by the root rot complex. Credit: Photo courtesy of Rafael Grajales.

Roping in rogue microbes

In this wild west, biology researchers are the cowboys, using science to rope in the invisible threats to livestock.

Dr. Andrew Cameron, a microbial geneticist and U of R associate professor in the Faculty of Science, leads research as a principal investigator with IMSS. His lab is developing rapid, practical tools to help producers identify harmful organisms in both water sources and livestock.

For Agribition, his team showcased their innovations in ruminant pathogen detection. Their pathogen detection panel uses more than 10,000 DNA targets to identify bacteria, viruses, and antibiotic-resistant genes in livestock samples, helping guide effective treatment. The panel also evolves with every new discovery, allowing the team to stay ahead in disease detection.

Laura Schnell, PhD Candidate under the supervision of Cameron, also shared her work on toxic blue-green algae. Certain algae can produce harmful toxins that can sicken or even kill cattle if they drink contaminated water. Current testing options don’t give producers the early warning they need, are expensive, require samples to be mailed to a lab, and only detect the toxin after it has already built up in the water which is often too late to prevent harm.

The team is working with Saskatchewan partners to develop an on-site test, similar to a COVID rapid test, that detects the genes responsible for toxin production. With earlier detection, producers can stay ahead of blooms and keep their livestock safe.

Cameron’s lab is keeping its lasso tight, stopping these microscopic outlaws from running wild on Prairie producers.

Saddle up and explore the cutting-edge research and degree programs in the Biology Department.

Congratulations to the researchers, students and labs who represented the U of R at Agribition. Their commitment to discovery and their passion for solving real-world challenges demonstrates the power science has to support communities and shape a brighter future.

About the University of Regina

At the University of Regina, we believe the best way to learn is through access to world-class professors, research, and experiential learning. We are committed to the health and well-being of our more than 16,600 students and support a dynamic research community focused on evidence-based solutions to today’s most pressing challenges. Located on Treaties 4 and 6—the territories of the nêhiyawak, Anihšināpēk, Dakota, Lakota, and Nakoda peoples, and the homeland of the Michif/Métis nation —we honour our ongoing relationships with Indigenous communities and remain committed to the path of reconciliation. Our vibrant alumni community is more than 95,000 strong and enriching communities in Saskatchewan and around the globe.

Let’s go far, together.